Parameter Tuning with Caret

One of the most important aspects of any model is its parameters. For

example, how do we know the ideal amount of trees for a random forest,

or the minimum number of observations needed in each node of a GBM?

Finding just the right parameters can take your model from good to

great… the question is (as with most things in life), how can I do

this without putting a ton manual of work into it? Well, this tutorial

shows us how to search for ideal model parameters using the caret

package we went over in a previous tutorial!

Data and Model Selection

To keep some continuity going, we’re going to again be using the shot

log dataset

(don’t worry, I’ll have something new for you guys soon!) as well as

model using a GBM. GBMs have a good amount of tunable parameters, so

they’ll be pretty good to illustrate this process. However, caret

works with MANY models, a list of which and their required parameters

for tuning can be found

here. As you can see if

you search through, gbm() from the gbm package is an available

method, so we don’t have to learn any new model intracacies.

We’re also going to just take a random sample of 5,000 observations because the methods we’ll be using today are pretty time expensive.

#Remember to specify where YOU saved it in your directory!

shot_log<- read.csv("~/R/examples/blog/January 2018/shot log.csv")

set.seed(1234)

shot_log<- shot_log[sample(1:length(shot_log$GAME_ID),

size=5000, replace = F),]

Modeling in Caret

If we go all the way back to August to the tutorial on caret and cross-validation, you might remember some specific set-up steps we had to use with caret. Well let’s jog your memory with some rehashing!

To begin, we should set up some control parameters for our model. This

is where we can specify the cross-validation method and set its

specifics. For example, let’s specify that we’ll use repeated

cross-validation with 5 folds and 3 repeats. Remember that this means

that our dataset will be split into 3 separate groups; a model will be

built on each possible combination of 4 groups, leaving one group out

each time to act as a test set. This process is repeated three times,

and the results are averaged. We’ll also specify the arguments

classProbs = T and savePredictions = T. This will save the

probability predictions for each resample and the predictions for each

resample respectively. Keeping these, we can see how the model performs

on each resample.

library(caret)

control<- trainControl(method = "repeatedcv", number= 3, repeats = 3,

savePredictions = T, classProbs = T)

Now here’s an additional step we didn’t go over in the cross-validation

tutorial: setting a tuning grid of possible parameters. These are

possible values for each parameter in the model. Let’s zoom in on a

specific parameter to illustrate: n.trees. Here, we specify either

250, 500, or 750 trees to build the model on. What we’ll essentially be

doing is building three cross-validated models, one for each of the

number of tree parameters. All other parameters would be held constant.

tune<- expand.grid(n.trees=c(250, 500, 750), interaction.depth=3,

shrinkage=.01, n.minobsinnode=15)

With these steps down, let’s build a model using caret. We’ll specify

method = "gbm" and set trControl = control and tuneGrid = tune.

set.seed(1234)

sl.gbm<- train(SHOT_RESULT ~ LOCATION + PERIOD + SHOT_CLOCK + DRIBBLES

+ TOUCH_TIME + SHOT_DIST + CLOSE_DEF_DIST,

data = na.omit(shot_log), method = "gbm",

trControl = control, tuneGrid = tune, verbose = F)

sl.gbm

## Stochastic Gradient Boosting

##

## 4811 samples

## 7 predictor

## 2 classes: 'made', 'missed'

##

## No pre-processing

## Resampling: Cross-Validated (3 fold, repeated 3 times)

## Summary of sample sizes: 3207, 3207, 3208, 3208, 3207, 3207, ...

## Resampling results across tuning parameters:

##

## n.trees Accuracy Kappa

## 250 0.6114461 0.1894305

## 500 0.6113078 0.1910675

## 750 0.6087440 0.1870155

##

## Tuning parameter 'interaction.depth' was held constant at a value of

## 3

## Tuning parameter 'shrinkage' was held constant at a value of

## 0.01

## Tuning parameter 'n.minobsinnode' was held constant at a value of 15

## Accuracy was used to select the optimal model using the largest value.

## The final values used for the model were n.trees = 250,

## interaction.depth = 3, shrinkage = 0.01 and n.minobsinnode = 15.

So looking at the output, we can see that the optimal model was the one

with 750 trees as it had the highest average cross validated accuracy.

We can also check out the accuracy measures of on each test fold from

our optimal model by calling sl.gbm$resample.

sl.gbm$resample

## Accuracy Kappa Resample

## 1 0.6203242 0.2096489 Fold1.Rep1

## 2 0.6038677 0.1717461 Fold3.Rep1

## 3 0.6184539 0.2042670 Fold2.Rep1

## 4 0.6153367 0.1983846 Fold2.Rep2

## 5 0.6169682 0.1986905 Fold1.Rep2

## 6 0.6115960 0.1871868 Fold1.Rep3

## 7 0.5985037 0.1624754 Fold3.Rep2

## 8 0.6150967 0.1986188 Fold3.Rep3

## 9 0.6028678 0.1738564 Fold2.Rep3

Now something to note is that you are losing some control with this

method. We can see having 750 trees lead to the model with the highest

average cross-validated accuracy, but the increase is pretty minimal

from 500; knowing how GBMs are prone to overfit, it may make more sense

to go with a smaller tree sample. It’s something to take into account,

but just know that using sl.gbm in predictions or future analysis will

be using the optimal 750-tree model.

We also aren’t limited to modifying one parameter at a time. We can adjust each parameter to find a model with an ideal combination. The thing to remember is that each combination of parameters requires a new cross-validated model to be developed, so having multiple values for multiple parameters can be very time consuming.

Let’s try adjusting not only ntrees, but also the shrinkage.

tune2<- expand.grid(n.trees=c(250, 500, 750), interaction.depth=3,

shrinkage=c(.005, .01, .05), n.minobsinnode=15)

set.seed(1234)

sl.gbm2<- train(SHOT_RESULT ~ LOCATION + PERIOD + SHOT_CLOCK + DRIBBLES

+ TOUCH_TIME + SHOT_DIST + CLOSE_DEF_DIST,

data = na.omit(shot_log), method = "gbm",

trControl = control, tuneGrid = tune2, verbose = F)

sl.gbm2

## Stochastic Gradient Boosting

##

## 4811 samples

## 7 predictor

## 2 classes: 'made', 'missed'

##

## No pre-processing

## Resampling: Cross-Validated (3 fold, repeated 3 times)

## Summary of sample sizes: 3207, 3207, 3208, 3208, 3207, 3207, ...

## Resampling results across tuning parameters:

##

## shrinkage n.trees Accuracy Kappa

## 0.005 250 0.6101290 0.1835858

## 0.005 500 0.6120694 0.1906208

## 0.005 750 0.6099910 0.1873153

## 0.010 250 0.6112381 0.1890034

## 0.010 500 0.6100602 0.1886463

## 0.010 750 0.6065961 0.1829372

## 0.050 250 0.6033401 0.1779944

## 0.050 500 0.5956497 0.1645173

## 0.050 750 0.5908680 0.1567981

##

## Tuning parameter 'interaction.depth' was held constant at a value of

## 3

## Tuning parameter 'n.minobsinnode' was held constant at a value of 15

## Accuracy was used to select the optimal model using the largest value.

## The final values used for the model were n.trees = 500,

## interaction.depth = 3, shrinkage = 0.005 and n.minobsinnode = 15.

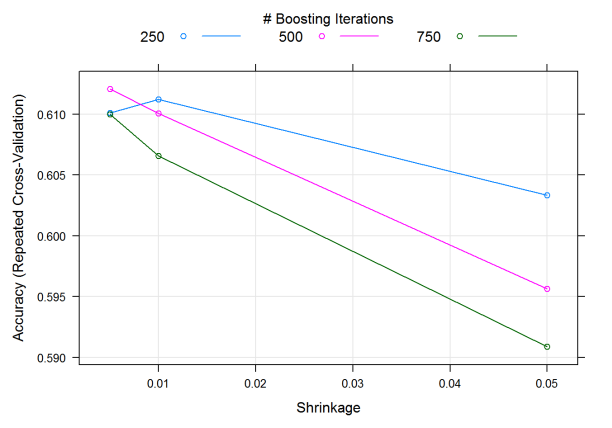

We can see that the model chosen has 500 trees and a shrinkage parameter of .005. The overall trend of how the model performs can be viewed graphically by simply calling plot on the output. Average cross-validated accuracy goes down as shrinkage increases (as expected!), with smaller tree amounts working better with larger shrinkage rates.

plot(sl.gbm2)

Finishing Up

Doing this whole process manually would’ve taken a lot of time and code. Using caret, this parameter tuning process can be automated. We do have to take into account that this is a fairly automated process, and really take a look at output to make sure it makes sense. That is a small price to pay, though, to find the best parameters for modeling!